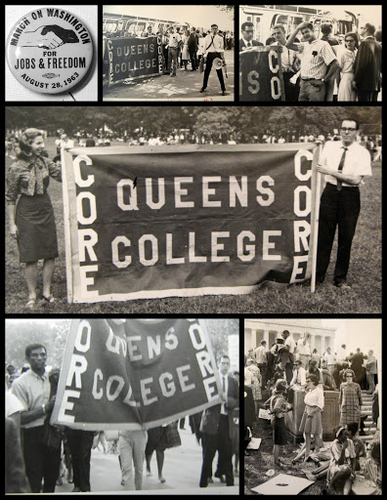

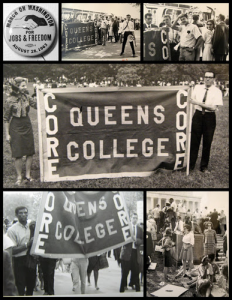

On Aug. 28, 1963, a bus full of young people from Queens College’s student association and Congress of Racial Equality drove to Washington, D.C. to be a part of a movement, to be a part of something greater.

“The general tone, particularly among young people was ‘hey the world’s changing and we can actually play a roll, we can make a difference,’” Mark Levy, QC SA President from 1962-1963, said.

Between the Lincoln Memorial and the Washington Monument, around 200,000 people gathered to participate in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

Levy, who is now special assistant to the president for the civil rights initiative and was a QC SEEK teacher, describes the march as very peaceful and exciting. He compared it to a church service because everyone wore their “Sunday best” knowing that the whole nation was watching.

Although many people are more familiar and remember this day as when Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech, the impact of this day brought a massive change to the United States, from civil rights to the labor movement.

“People went for many different reasons; King’s ‘I have a dream’ speech, he talks about the southern movement,” Levy said. “One of the things that gets forgotten when we talk about the march on Washington was that the demands around economic equity were primary. It wasn’t freedom and jobs, it was jobs and freedom.”

At the time, jobs were seldom, especially for people of color. There was a struggle to obtain jobs and issues began to arise from all across the nation.

“Each city or region had its own set of issues which were related and they formed a coalition around that and the slogan was: jobs and freedom,” Levy said, describing how the march got its name.

Prior to the march in 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court case, Brown v. Board of Education, ruled that public schools were to be desegregated, but many schools in the south did not abide to this ruling. In June of 1963, QC students from Student HELP were making their way down south to partake in their summer tutoring project in segregated Virginia.

After their project was over they headed back north and attended the march as well. Levy claims that the different QC groups were able to meet in Washington and bring together southern and northern issues.

Fifty years ago, the environment at QC was extremely different than how it is today. For one thing there was no tuition and the college was not as diverse, barely any students of color were present.

In Rosalyn Terbong-Penn’s 2009 essay “Queens College Black Students: Fighting for 1960s Civil Rights on Campus and Off,” she says that as a black QC student in the sixties, she faced many prejudices at the college, including not receiving the grade that she deserved simply because of her skin color.

“We did not get it at first, because we had earned our acceptance into QC with high scores on the regents exams and high grade point averages,” Terbong-Penn states in her essay, referring to why blacks were being treated unfairly in academia.

Terbong-Penn trained QC students to head down south to Prince Edward County, Virginia to tutor other students.

In reference to the president at the time, John F. Kennedy, Levy likes to refer back to his inaugural speech when Pres. Kennedy stated, “Ask not what your country can do for you, but ask what you can do for your country.”

“I think the common theme from the march on Washington is that young people and people sticking together can make a difference and change the world,” Levy said.