Following the success of recent movies such as “12 Years a Slave” and “Django Unchained,” critics asked whether another story about slaves was really necessary.

After reading “Song of the Shank” by Jeffrey Renard Allen, New York Times book reviewer Mitchell S. Jackson felt compelled to answer with a resounding “yes.”

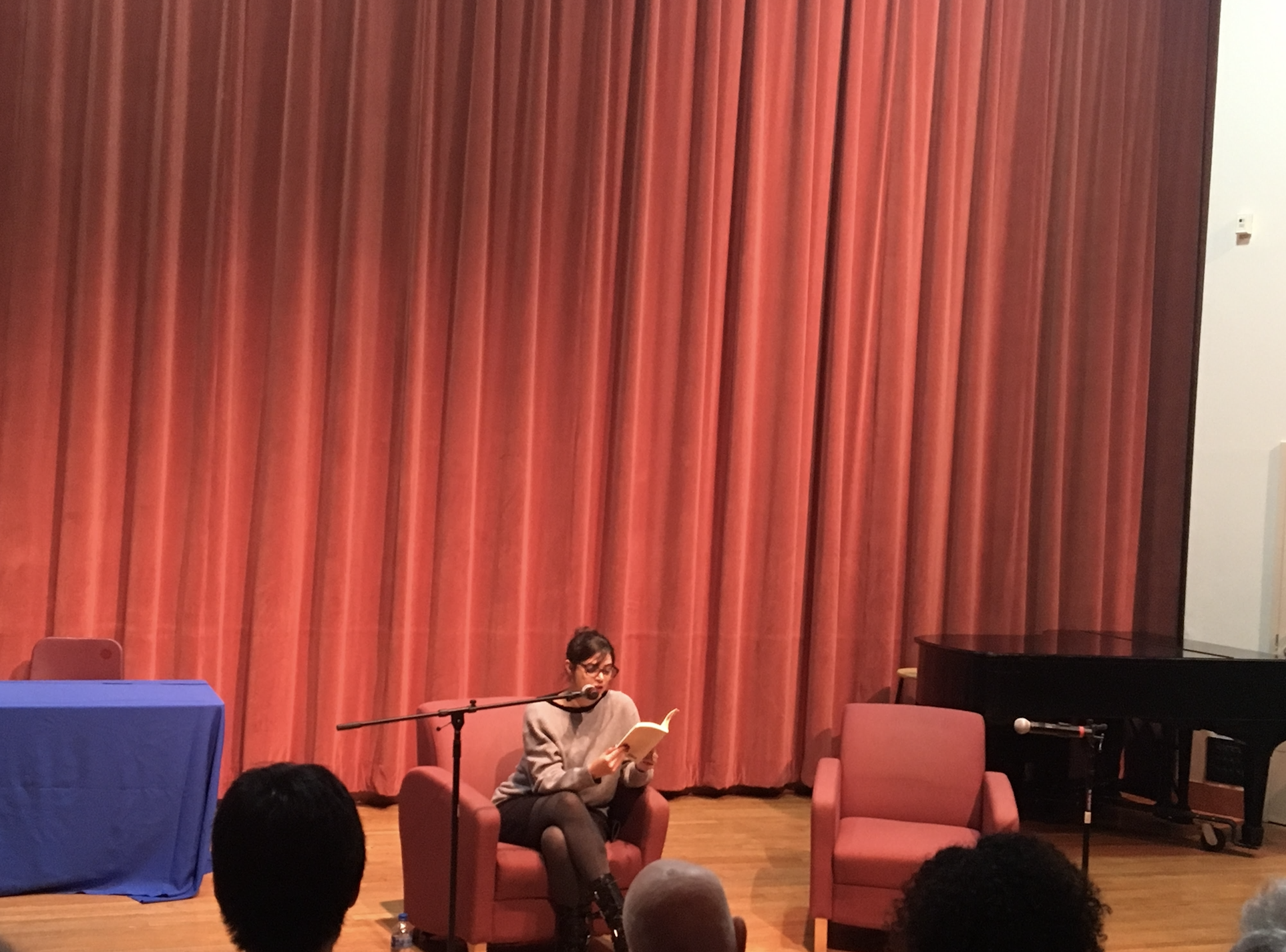

On Nov. 11, Allen discussed his latest work as part of Queens College’s 39th Anniversary Evening Reading Series. “Song of the Shank” is the reimagined and fictional biography of “Blind Tom,” one of the 19th centuries most prominent performers and the first black person to play at the White House at the age of 10.

Blind Tom, born as the slave Thomas Wiggins in 1849 Georgia, rose to fame at the age of 6 as a blind piano prodigy. Despite his fame and celebrity, both historians and musicians alike seem to have largely forgotten him.

Allen, an English professor at QC, pieces together the life of the historical figure through the nonlinear narratives of others. The novel is fiction, however, and Allen boldly and fearlessly creates a 19th century setting from his own imagination.

The narratives follow Tom from his childhood as a slave to his years under different managers trying to exploit him, and finally as he reconnects with his mother on the fictional island of Edgemere during the period of Reconstruction. Allen’s focus is less on the historical facts surrounding Wiggins and more on Blind Tom’s cultural significance.

“The most important thing is that this is a person who was a celeb of his own time–[he] might have been the most famous pianist of the 19the century– and he essentially disappeared from history… I think the most important thing is to be aware that he existed and his impact on the time,” said Allen.

Allen also stressed during his interview that the story is not as much about historical slavery in America as it is about Reconstruction and the theoretical concept of being free. Allen referred to Reconstruction as a time reflecting “failure of American democracy.”

While slavery is an often explored theme in the entertainment and art industries, Reconstruction is not often discussed. Allen’s island of Edgemere portrays the plight of newly freed slaves and Southern refugees with blistering honesty.

At first glance, the achievements of Blind Tom as a pianist and celebrity appear to be an impressive feat, breaking through boundaries created for him by his race and disability. Being blind, Tom is the only one unaware that his skin color creates constraints and this is perhaps what allows him to achieve success. However, Allen does not let the reader forget that even as a performer at the White House, Tom was still a slave.

African Americans in the novel question whether or not Blind Tom was “aiding the race or harming it.” At one of his first performances in pre-Civil War south, an audience member remarked not on his musical genius but rather on how he was the ideal slave who would “do what you tell him with his eyes closed.”

His owner even uses the proceeds from Tom’s performances to fund the secessionist cause leading to the Civil War. It can be argued that Tom is the “last legal slave in America,” even once emancipated.

“Song of the Shank” ties together the broken narratives of characters and historical figures that mainstream media has largely ignored, if not forgotten. As he details Tom’s life and his exploitation, however, Allen leaves readers with many unanswered, but hardly unwelcomed questions about morals, race, class, and history.

To the critics who say that there is more than enough material on slavery, the premise of “Song of the Shank” responds that that is not the case by posing the question: why has history forgotten about Blind Tom?