On January 5th, New York Governor Kathy Hochul announced her proposal for the “Interborough Express” (IBX), a new rail service that will connect Brooklyn and Queens. If completed, this will be the largest expansion of rapid transit service in the city since the opening of the Sixth Avenue Subway in 1940. To truly understand the impact this line will have, however, we must first understand how we got to our current situation and why new rapid transit is so important, particularly in Queens.

The first thing to unpack is why the outer boroughs have sparser subway service in general. According to QC History Professor Kara Schlichting, subways were originally independent commercial corporations, starting in Manhattan and slowly expanding towards the outer boroughs. Regarding Queens, Schlichting notes that “Transportation is the reason why Queens develops so rapidly in the teens, twenties, and thirties…You can watch the density of Queens change as rapid transit arrives.”

To real-estate developers, ease of transit was a crucial selling point of their properties in Queens. “How does a real estate developer make money?” Schlichting asks, “They have to sell their properties or have to have renters in their properties. How do you attract people to your properties? You have amenities. Today it might be a rooftop pool in Long Island City but in the past it was ease of rapid transit.”

Even today, however, transit access is still a crucial part of real estate value. As Schlichting notes, “Rents are cheaper the farther you are from rapid transit.” Over the course of the 20th century, some avenues of transit like the streetcars were disbanded and subway expansion halted, leaving many areas of Queens and Brooklyn underserved by rapid transit access. In addition, a Manhattan-centric service pattern inhibited commuting between the outer boroughs.

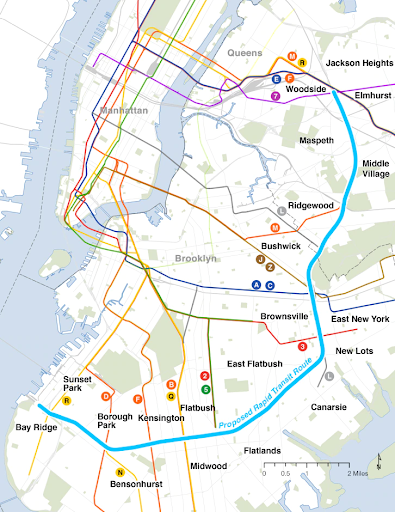

The Interborough Express proposal is a result of an attempt to practically address these two issues. The line will mainly use the Long Island Railroad Bay Ridge Branch, an existing freight rail line, for operations. Using an already existent line greatly increases the cost-effectiveness and workability of the project.

That’s not to say that there aren’t challenges. A study released by the MTA in January notes such issues as height restrictions, width constraints along the line, and complex intermodal connections in some places between IBX and other subways and buses.

One major impact is that IBX will shorten commutes by providing a much more direct path between outer-borough destinations. As QC Urban Studies Professor Dwayne Baker points out, “If you look at New York’s transit system, there is only one subway line, the G Line, that does not go through Manhattan. This [new line] is possibly going to alleviate some of the strain… on the existing system.”

Moreover, when looking at the route of the proposed system, there are many potential connections to other subway lines available along the route, opening up new commuting possibilities. Equally important is its role in bringing service and connections to current “transit deserts” such as Maspeth, Queens. Baker, however, cautions that, “with any new development, you may price out people from those areas that are already there, so hopefully there is a part of the plan that helps maintain at least rent prices in those areas.”

Will IBX happen or will it be consigned to the large waste bin of failed NYC transit proposals? To Baker, the difference is in politics. “It has a lot to do with political power,” he says, “Governor Hochul has come out and really pushed this plan…the [other plans] were really mostly nonprofit and transit advocacy groups who may not have the political power to wish this.” Time will tell if Baker’s analysis is proven correct.