When Queens College Evening Readings started some thirty-six years ago, after each event, I’d invite the entire audience back to my apartment. There would be about eighty to a hundred of us in my small, one-bedroom duplex, with wall–to-wall people—most of them students—pressed up against each other in my kitchen, my living room, my bedroom and on the stairs between the two small floors. The author would usually join us as well. And as the drinking age was then eighteen, people would usually bring wine. A lot of wine.

Each night was a party, a literary party, with students and faculty hanging out with the author until one or two in the morning. Sometimes we went to Marie Ponsot’s house—which was a lot bigger than my apartment—and still the place was packed. Marie was, and still is, an amazing poet (Marie is now 91), and one of the greatest teachers ever to have taught at Queens or anywhere else. Students would often sit on the floor of her office (which was also my office) just to be in her presence. And a small community of student writers (and readers) grew up around her. In fact, the Evening Readings series itself grew out of that small community of students. And Marie was the first writer to read in the series, back in the spring of 1976.

This went on for quite a while—parties with the author and the audience at my home or Marie’s—until Allen Ginsberg read here, and 500 people showed up. There was no way I could invite 500 people back to my apartment, and I knew then that the series had changed.

Snapshots from those early years. I remember Edward Albee sitting in my beat up 69 Dodge Dart with the ripped up seats, the hole where the radio should have been, the window that didn’t close all the way (in winter, the wind and snow blew in)—but Edward loved it. I remember Ralph Ellison in that same dilapidated car—I think he felt sorry for me, and for English teachers everywhere (and our meager salaries): he donated his honorarium to the English department library.

I remember Jamaica Kincaid the first time she read here. She collapsed on stage. She had fainted, and I helped her up off the floor, off the stage, and into the lobby, where we sat for a little while. Then she made her way to the restroom where, she said, she threw up. After which, she came back and finished the reading. Years later, Jamaica would tell me that the first reading she ever gave in her life was that night here at Queens.

I remember Arthur Miller at his 85th birthday tribute. He had fallen only a few days before and cracked several ribs, but Frank McCourt was so outrageously funny that night, Arthur couldn’t stop himself from laughing over and over and over again, even though it hurt like hell. I remember time slowing and the night coming alive during an interview I did with Czeslaw Milosz; then at the restaurant afterwards, Czeslaw drinking three glasses of vodka in quick succession. He was eighty-eight years old. I remember two Eastern European émigrés in the audience deciding to take a photograph with the author—during an event—the husband actually walking up on the stage, the wife with the camera, motioning the husband to get closer, and Isaac Beshevis Singer slowly raising his head from the page, in bewilderment.

I remember Galway Kinnell in 1976, reading “Little Sleep’s-Head Sprouting Hair in the Moonlight,” a poem about a father looking at his baby in its crib at night, the final stanza of which reads:

Little sleep’s head sprouting hair in the moonlight,

when I come back

we will go out together,

we will walk out together among

the ten thousand things,

each scratched too late with such knowledge, the wages

of dying is love.

After the reading, I wrote Galway a long, youthfully exuberant letter, arguing that the last line of the poem should be changed from “each scratched too late with such knowledge” to “each scratched in time with such knowledge.” And Galway wrote back: “I tried reading it so once & it sounded good—I thank you.” And he changed the line to read that way in all subsequent editions of his Selected Poems.

I remember interviewing W.G. Sebald in the spring of 2001 (with Arthur Miller, Peter Carey, and Susan Sontag in the audience). It was intense. We locked eyes. I felt in sync with him, on stage, backstage, and in the car afterwards. A little while later, he sent me a postcard from his home in England. “The best part about being in New York,” he said, “was talking to you.”

Later that same year, Sebald died in a terrible car accident. Which was overwhelming.

Some time after that, a reporter for The New York Times told me that when he had asked W.G. Sebald whom he should speak to to get a better grasp of his work, Sebald had told that reporter to speak to me. When I heard this, months after he had passed away, it was very moving.

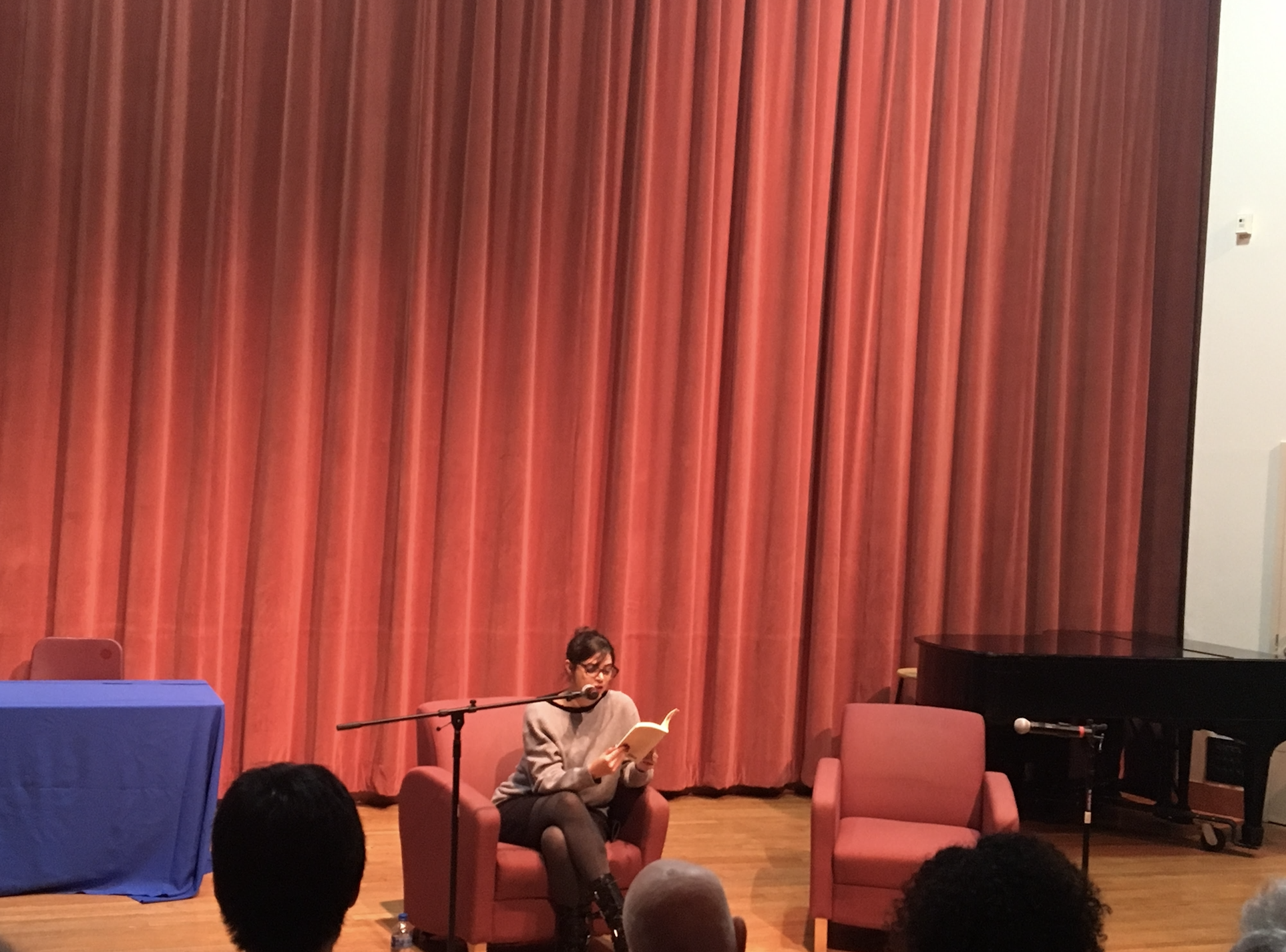

I remember talking to students who were thrilled—who told me they were thrilled—to meet an author like Joyce Carol Oates or Edwidge Danticat or Peter Carey or Mary Gaitskill or Ha Jin or E.L. Doctorow at a small reception here on campus, or to hear an author like Nicole Krauss or Margaret Atwood or Stephen Sondheim or David Grossman or Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie speak on stage. I also remember more than one of those students telling me that the experience had changed her life.

At about fourteen or fifteen when I first started reading serious literature, it changed my life. Literature gave me a way to look at my life, and at the people around me, a way to think about the unthinkable, about death and love and loss and parties and endless, impossible nights. Even today, reading a great novel or story or poem or play, or meeting a great author can change me; it continues to change me. And to hear a student say that she has had something of that same experience, well, this, in the end, this is everything.

Joseph Cuomo is the Director of Queens College Evening Readings, which he founded in 1976. For more information about the Evening Readings, visit www.qcreadings.org.